Jason Berry’s ‘City of a Million Dreams’ documentary illuminates New Orleans jazz funerals

The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate

By Keith Spera

New Orleans journalist, author and documentarian Jason Berry spent much of his recent trip to the Heartland International Film Festival in Indianapolis commiserating.

For years, he labored to bring “City of a Million Dreams,” his lyrical study of New Orleans’ jazz funeral traditions, to life, struggling with funding challenges, a disastrous hurricane and the death of a main character.

Swapping similar stories with other indie filmmakers at Heartland “cushioned the bruises a bit,” Berry said this week. “This has been an epic in my life.”

That epic, the 89-minute “City of a Million Dreams,” will have its hometown premiere Wednesday at 7 p.m. at the Broadside, the outdoor venue near the Broad Theater, as a prelude to the New Orleans Film Festival’s November opening. Berry and other principals will conduct a post-screening question-and-answer session.

Admission is free for New Orleans Film Society members and festival passholders; tickets are also available for purchase.

“City of a Million Dreams” shares a title and some material with Berry’s 2018 book, which examined 300 years of New Orleans history through the lens of music, culture and race.

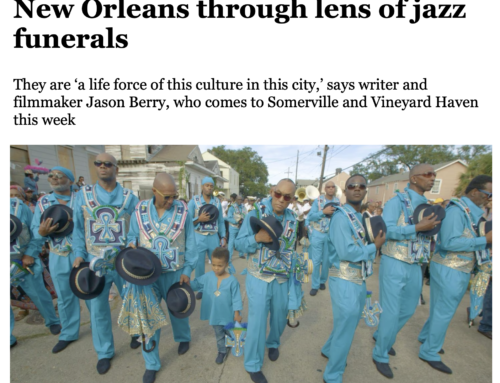

Traditional jazz clarinetist Dr. Michael White bridges the book and the film. He and the late Deborah “Big Red” Cotton, a tireless advocate for and chronicler of second-line culture, are the documentary’s dual protagonists; their stories frame the narrative. Fred Johnson, of the Black Men of Labor Social Aid and Pleasure Club, and trumpeter Gregg Stafford are also prominently featured.

For Berry, “City of a Million Dreams” is in keeping with his lifelong fascination with matters of religion, music and New Orleans.

He first stepped onto the national stage with his 1992 book “Lead Us Not Into Temptation: Catholic Priests and the Sexual Abuse of Children,” which largely exposed the extent of the church’s cover-up.

By the late 1990s, he’d started researching and filming New Orleans jazz funerals. He interviewed White, Stafford and Olympia Brass Band leaders Milton Batiste and Harold Dejan. Batiste and Dejan spoke of how the beauty and spirituality of the tradition were threatened by the crack epidemic, the related surge of drug-related killings and a trend toward less structured funeral processions.

He received a grant from the Ford Foundation to film an oral history about jazz funerals and second-lines, followed by a Guggenheim grant for additional research.

Other projects then intervened. The explosive 2001 Boston Globe series about abusive Catholic clergy and cover-ups pulled Berry back into that world. He wrote a second book on the subject, 2004’s “Vows of Silence,” which he adapted into a film.

All along he kept the embers of his “parading for the dead” project burning. If he was in New Orleans during a jazz funeral, he filmed it.

Hurricane Katrina steered the jazz funeral documentary in a different direction, as Berry and cameraman Philip Braun documented White’s first visit to his ruined Gentilly house.

By 2015, with the reform-minded Pope Francis leading the Catholic Church, Berry was ready to move on from the “Vatican stuff” and focus on jazz funerals.

“I didn’t think I had any more insights to make unless I figured out a way to live in Rome full time,” he said. “But I felt a gravitational pull back to New Orleans.”

He explored how the evolution of funeral traditions mirrored the broader history of New Orleans in “City of a Million Dreams: A History of New Orleans at Year 300,” the book he released in conjunction with New Orleans’ 2018 tricentennial.

Berry writes in the book that “City of a Million Dreams” is also the title of a song by Irish Channel jazz musician Raymond Burke that is a favorite of White’s.

The book’s themes and research carried over to the film. Berry slogged through the “arduous” process of fundraising for the film’s nearly $1 million budget. Former Jesuit High School classmates, including Bernard Pettingill Jr., and various foundations came through with timely contributions.

Tim Watson, who has edited numerous locally shot documentaries, signed on as co-writer and co-producer. “Tim’s fingerprints are on every frame,” Berry said.

Berry’s daughter Simonette, who works as a set artist in the film industry — she built the time machine that transports Arnold Schwarzenegger’s character in a latter-day “Terminator” film — is also a co-writer and co-producer.

“It really is a homegrown film,” Berry said.

The Archdiocese of New Orleans granted permission to film in church-owned cemeteries. Berry leaned heavily on local archives, including the Historic New Orleans Collection, which provided historic footage by photographer and New Orleans jazz aficionado Jules Cahn.

“Jules told me that funerals in the ’60s were more like urban ballets,” Berry said. “When we started looking at his footage, there were so many moments of poetry in motion. He really had an eye.”

Berry also used his own footage of White and Stafford going back 25 years: “You see them change on screen from young men to older men.”

The documentary’s most ambitious shoot was an elaborate re-enactment of the drum and dance rituals enslaved Africans performed at Congo Square. Monique Moss, an adjunct professor of dance at Tulane University, choreographed dozens of dancers and drummers for the three-day shoot in 2018. Those drummers included Congolese master Titos Sompa and Seguenon Kone, an Ivory Coast native now based in New Orleans.

“Monique orchestrated all that in a way that was breathtaking,” Berry said.

Deborah Cotton, who blogged about second-lines for Gambit Weekly, was one of 20 people wounded during a mass shooting at a second-line parade on Mother’s Day 2013. Cotton would later ask for leniency for the young shooters, even as she underwent dozens of surgeries to repair the damage they caused.

“To me, she was voicing the message of Pope Francis of ‘radical mercy,’” Berry said. “That really moved me.”

Berry hired Cotton as an advising producer on the film. She provided parade footage and also appeared onscreen.

“Deb was a star in the firmament,” Berry said. “So much color, so much zest. She was a life force, she really was.”

Then came the day in 2017 that Berry went to Cotton’s house for a meeting, and she wasn’t there. She’d been hospitalized for lingering complications from the shooting. Weeks later, she died.

“I did not realize the seriousness of her condition,” Berry said.

He and his co-writers considered how to treat Cotton’s death in the documentary. “Filming her funeral was really tough for all of us. We were all so crazy about her. Her death jolted me.”

From his early jazz funeral research 25 years ago, through numerous career detours, to the film’s release, “City of a Million Dreams” has been Berry’s odyssey.